Guiding businesses through the labyrinth of financial management, the vital tool known as the balance sheet stands as an indispensable navigator. Often deemed a snapshot of a company’s fiscal health at any given point, it illuminates the intricacies of assets, liabilities, and equity.

This article primarily focuses on templates of balance sheets, enabling readers to comprehend the structure, adapt according to their requirements, and enhance their financial proficiency. Let’s embark on this journey to decode the elements of this financial statement and provide insights into creating, reading, and interpreting it effectively.

Table of Contents

What Is a Balance Sheet?

A balance sheet, a fundamental financial statement in business, reflects a company’s financial position at a specific point in time by outlining its assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity. The assets denote what the company owns or controls, like cash, inventories, and property. Liabilities illustrate what the company owes, such as loans and payables.

Shareholders’ equity represents the residual interest in the assets after deducting liabilities, showing the owners’ claim on the company’s resources. By adhering to the fundamental equation, Assets = Liabilities + Equity, a balance sheet ensures the company’s financial equilibrium, thereby serving as a crucial barometer of its financial health and sustainability.

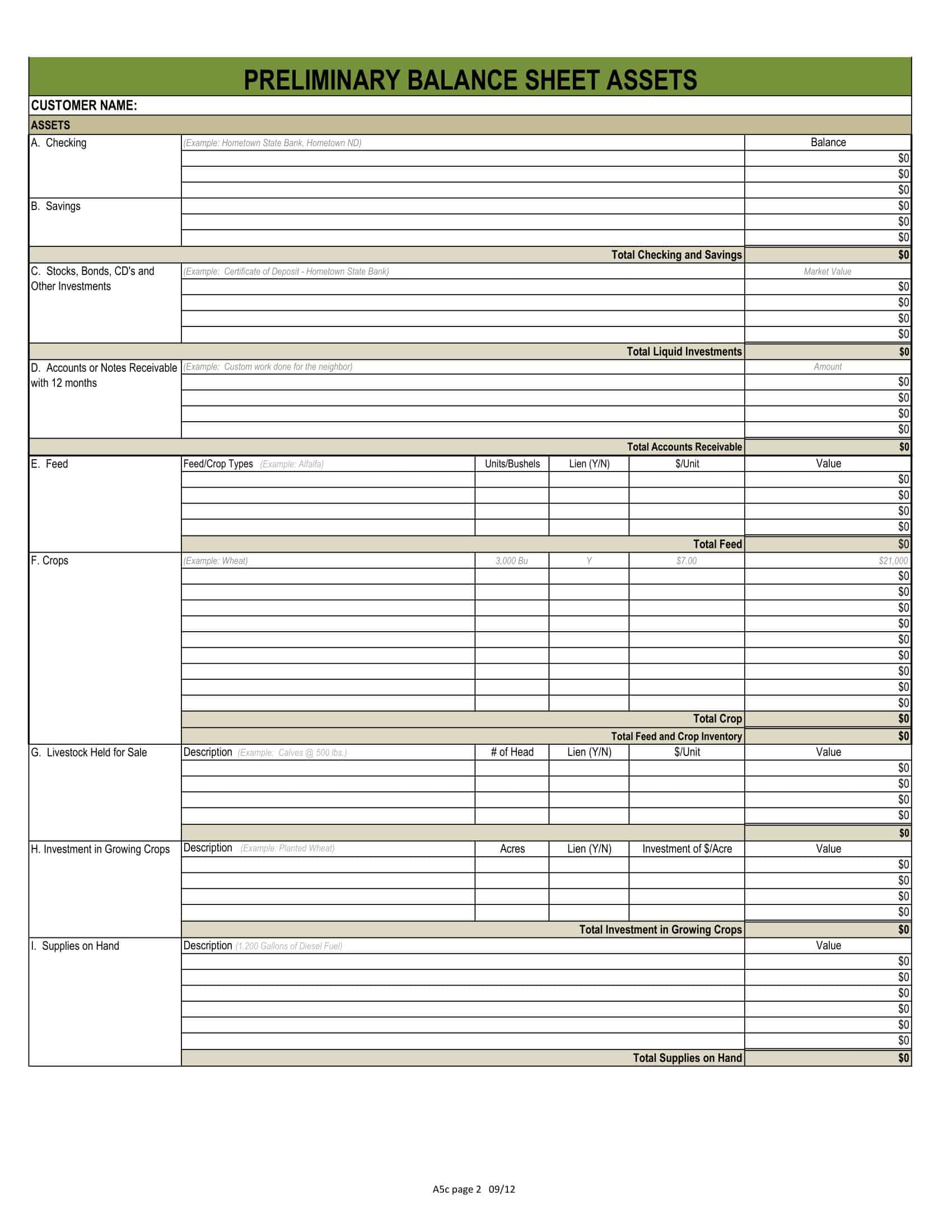

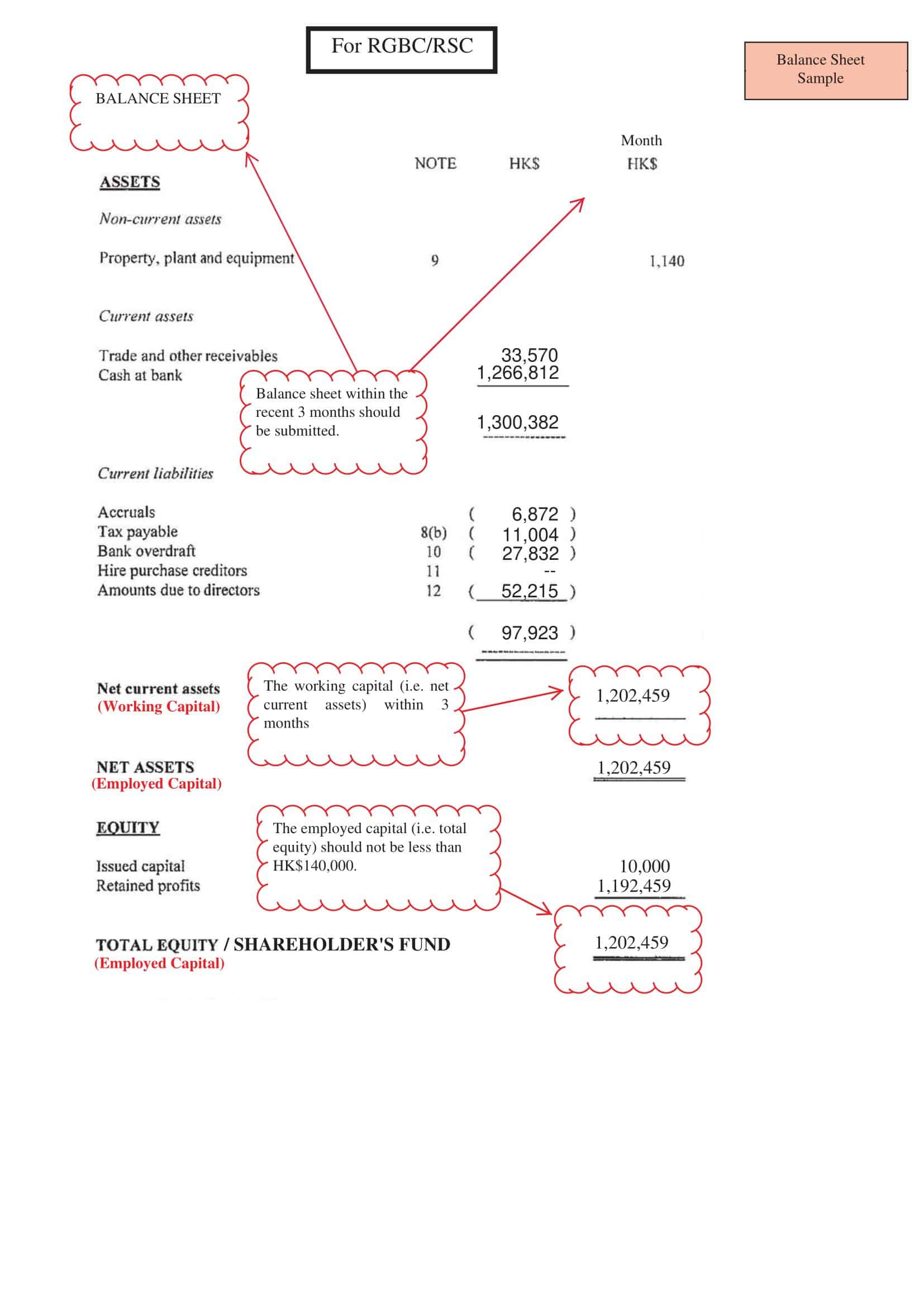

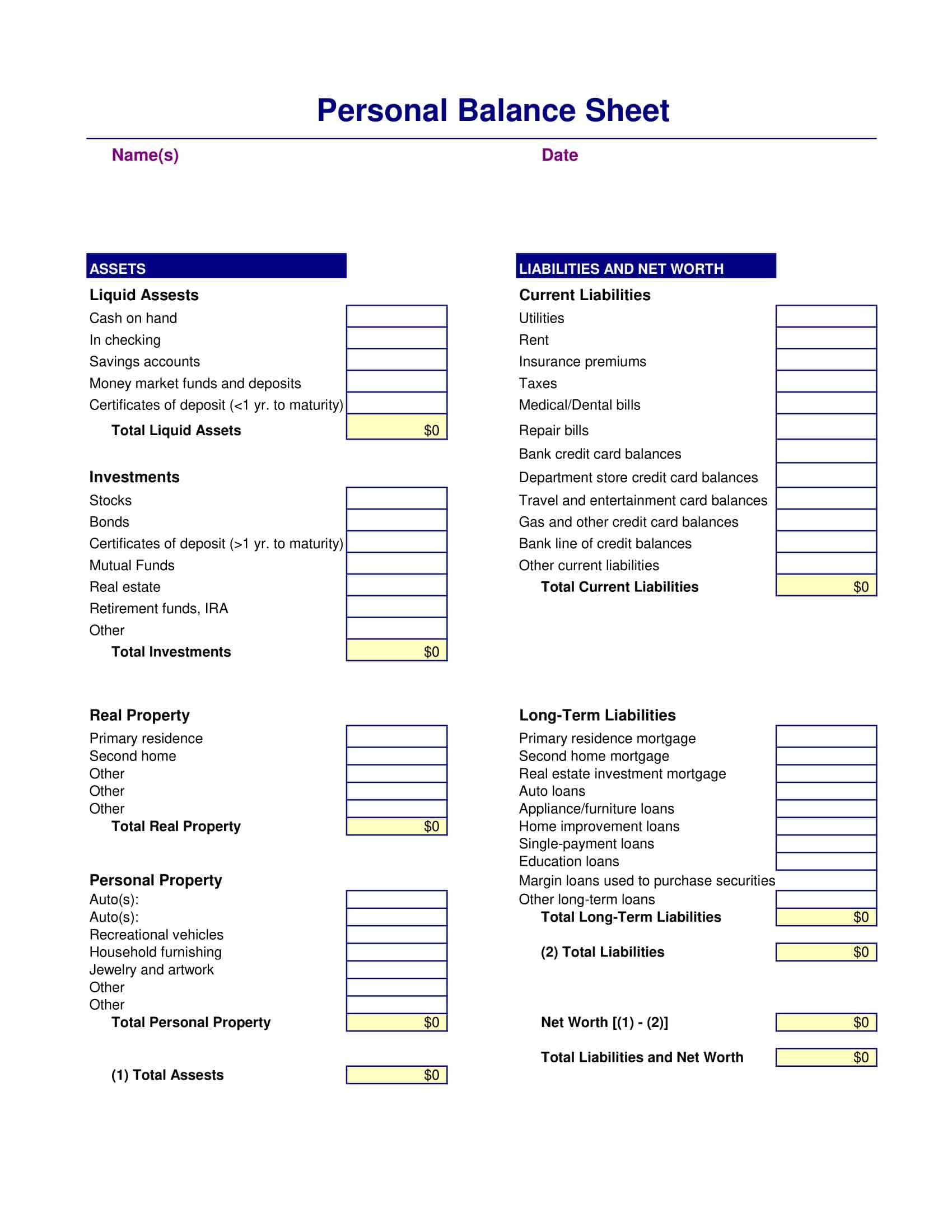

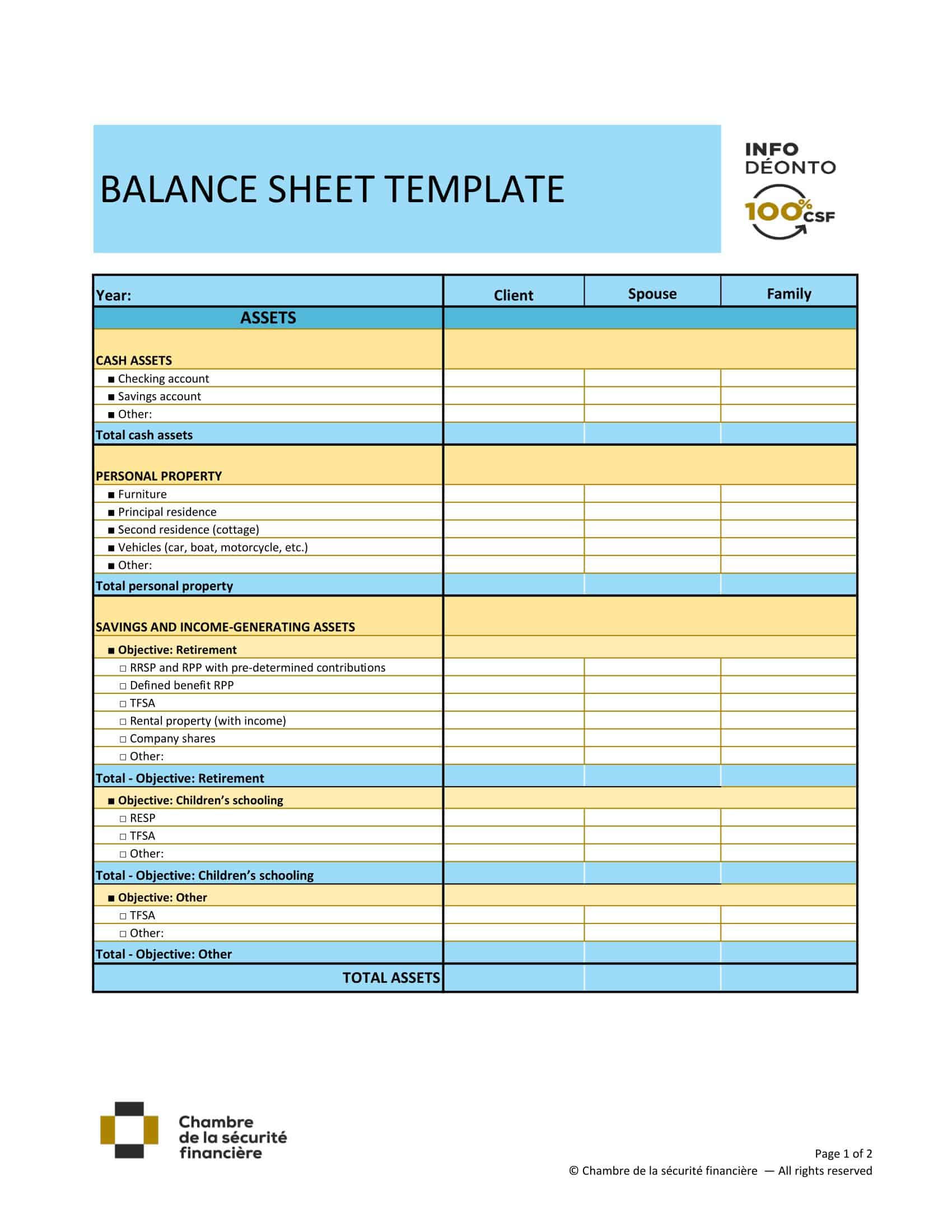

Balance Sheet Templates

Balance sheet templates are preformatted tools that facilitate the process of creating a balance sheet, a critical financial statement in business operations. They help to display a company’s financial health at a given point in time, showcasing assets, liabilities, and shareholders‘ equity.

Balance sheet templates typically come in the form of Excel spreadsheets or similar digital formats. They have predefined sections for assets (both current and fixed), liabilities (both current and long-term), and equity. Some templates include built-in formulas to calculate totals automatically, aiding accuracy and efficiency.

These templates offer a systematic way to record and analyze financial information. They can assist in making informed decisions, planning for the future, and identifying potential financial issues before they become problematic.

What is the Purpose of a Balance Sheet?

The primary purpose of a balance sheet is to provide a detailed snapshot of a company’s financial condition at a specific point in time. It serves as a reliable source of information for company management, investors, creditors, and other stakeholders, revealing the company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity.

This financial statement thus aids in critical decision-making, from strategic planning and performance evaluation within the company, to investment and credit decisions by external parties. Furthermore, by illustrating a company’s liquidity position, debt structure, and operational efficiency, it helps in identifying potential financial risks and opportunities. Hence, a balance sheet is a cornerstone of corporate financial reporting, contributing significantly to financial transparency and accountability.

Why Is a Balance Sheet Important?

The importance of a balance sheet in any business or financial environment can’t be understated, and here’s why:

- Snapshot of Financial Health: At its core, a balance sheet gives a snapshot of a company’s financial condition at a specific moment. It allows anyone, be it a manager, investor, or creditor, to quickly grasp the company’s financial situation by providing key figures related to assets, liabilities, and equity.

- Decision Making Tool: The balance sheet is an invaluable decision-making tool. By evaluating assets, liabilities, and equity, managers can make informed choices about the company’s strategy. It can guide investment decisions, provide insight into potential risk areas, and assist in setting targets and planning for future growth.

- Investor Attraction: A robust balance sheet can attract investors. By showing a high amount of assets relative to liabilities, a company demonstrates financial strength, which can lead to increased investment. It’s an essential document for potential investors to scrutinize before they decide to invest in a company.

- Lender’s Trust: Lenders rely heavily on balance sheets. It helps them understand a company’s ability to repay borrowed funds. If a company has more liabilities than assets, it may be a sign of financial distress, making lenders hesitant to extend credit.

- Regulatory Requirement: Balance sheets are a part of standard financial reporting, necessary for tax purposes and as a regulatory requirement. It helps regulatory authorities monitor a company’s operations and ensure the business is complying with the laws and regulations.

- Performance Measurement: Balance sheets, when compared over time, can give an excellent perspective on a company’s performance. It can reveal trends and offer insights into how effectively the company is managing its assets and liabilities.

- Risk Assessment: A balance sheet aids in identifying financial risks. A high debt load or lack of liquidity might indicate potential trouble. Similarly, stagnant or declining equity could be a sign that the company isn’t growing as it should.

- Asset Management: Through a balance sheet, a company can monitor and control its asset use. For example, it can identify obsolete inventory, analyze its receivables, and assess whether it’s making the best use of its assets.

- Shareholder Relations: A balance sheet also plays a key role in managing relations with shareholders. It provides the necessary transparency about the company’s operations and financial condition, helping build trust and confidence among the stakeholders.

In summary, a balance sheet acts as a mirror, reflecting the financial state of a business. It’s a dynamic tool that not only charts the financial direction of a company but also allows for proactive measures to ensure the business stays financially healthy.

Who Uses Balance Sheets?

Balance sheets are vital tools used by a range of individuals and organizations, each with their unique perspectives and objectives. These include company management, investors, creditors, financial analysts, and regulatory authorities.

Company Management

A company’s management team, including the CEO, CFO, and other top executives, use the balance sheet to gauge the business’s financial health and make strategic decisions. The balance sheet informs them about the liquidity position (the ability to meet short-term obligations), the capital structure (the mix of debt and equity), and the efficiency of asset use. For instance, if the inventory levels are consistently high compared to sales, management might need to review its inventory management practices.

Investors and Shareholders

Existing and potential investors examine the balance sheet to assess the company’s financial strength and stability. It can provide insight into many aspects of the business, such as its ability to generate cash flow, its level of indebtedness, and its growth potential. For example, a high ratio of debt to equity may signal a high level of financial risk, potentially discouraging potential investors. On the other hand, a company with a strong balance sheet boasting significant assets and minimal liabilities could be an attractive investment proposition.

Creditors and Lenders

Banks, bondholders, and other lenders scrutinize the balance sheet to evaluate a company’s creditworthiness before approving a loan or other forms of credit. The balance sheet shows them how much a company already owes to others (its liabilities), what it owns (its assets), and the amount of investment by owners (equity). A company with a high proportion of liabilities compared to assets may struggle to attract additional lending, as it may represent a higher risk of default.

Financial Analysts

Financial analysts use the balance sheet, among other financial statements, to conduct ratio analysis, trend analysis, and comparative analysis. Analysts rely on the balance sheet to calculate financial ratios such as the current ratio (current assets divided by current liabilities) which indicates a company’s ability to pay off its short-term liabilities. For example, a current ratio below 1 might suggest that the company could have problems meeting its short-term obligations, which could be a red flag.

Regulatory Authorities

Government agencies and regulatory bodies like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) require companies to file their balance sheets to ensure compliance with financial reporting standards. These documents help maintain transparency in the financial system and protect investors by preventing fraudulent activities. If a company’s balance sheet shows signs of financial mismanagement or potential insolvency, regulators may intervene to protect shareholders’ interests.

Suppliers and Trade Creditors

Suppliers and trade creditors are also interested in a company’s balance sheet. For instance, a supplier might review a potential client’s balance sheet to determine whether it’s safe to extend trade credit — an agreement to provide goods or services in advance of payment. If the balance sheet reveals a high level of short-term liabilities compared to assets, the supplier might insist on cash on delivery rather than offer credit terms.

Employees and Labor Unions

Employees and labor unions might also examine a company’s balance sheet to assess its stability and ability to meet future obligations like wages, healthcare, and pensions. For example, if the balance sheet shows that a company has significant retained earnings and a low debt ratio, it might suggest that the company is financially healthy and capable of meeting its commitments to employees.

Customers

Large customers or clients, particularly in business-to-business transactions, might review a company’s balance sheet before entering into contracts. This can be especially true for long-term contracts or agreements that require substantial investment or dependency. For example, a client planning to contract a company for a multi-year service might review the company’s balance sheet to ensure it’s likely to remain in business for the duration of the contract.

Competitors

Competitors may examine a company’s balance sheet to understand its financial strategy and strength. This can inform their own strategic decisions about things like pricing, marketing, or expansion. If a competitor’s balance sheet shows significant investment in fixed assets like machinery or property, it might indicate an intention to increase production or expand operations.

Acquirers and Merger Partners

If another company is considering acquiring or merging with a company, it will conduct a thorough review of the target company’s balance sheet. This review can reveal potential benefits and risks, inform the purchase price, and indicate whether the acquisition or merger would likely be a good strategic fit. For example, if the target company’s balance sheet reveals a high level of debt or few tangible assets, the acquirer might reconsider the deal or negotiate a lower price.

Components of a Balance Sheet

A balance sheet, one of the fundamental financial statements, comprises three primary components: Assets, Liabilities, and Shareholder’s Equity. Each component plays a unique role in providing a comprehensive overview of a company’s financial health.

Assets: Assets are resources owned or controlled by a company, from which future economic benefits are expected. Assets are often classified into two broad categories – Current Assets and Non-current (or Long-term) Assets. Current assets, like cash, accounts receivable, and inventory, are expected to be converted to cash or used up within one year or one operating cycle.

For example, accounts receivable represents the money owed to the company by its customers. Non-current assets, such as property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), long-term investments, and intangible assets like patents or trademarks, are expected to provide benefits for more than one year. PP&E, for example, includes the buildings, machines, and vehicles used in the company’s operations.

Liabilities: Liabilities represent the company’s obligations, or what the company owes to others. Like assets, liabilities are divided into Current Liabilities and Long-term Liabilities. Current liabilities, such as accounts payable, wages payable, and short-term loans, are obligations due to be settled within one year. For instance, accounts payable represents the money the company owes to its suppliers. Long-term liabilities, such as bonds payable or long-term lease obligations, are obligations due after one year. For example, bonds payable refers to the long-term debt issued by a company to its bondholders.

Shareholder’s Equity: Also known as owner’s equity or net assets, shareholder’s equity is the residual interest in the assets of the entity after deducting liabilities. In other words, it represents the amount that would be returned to shareholders if all the company’s assets were liquidated and all its debts repaid. Equity is usually divided into two parts: share capital (or contributed capital), which is the money that shareholders have invested in the company, and retained earnings, which is the cumulative net income that the company has earned over its life, minus any dividends distributed to shareholders.

A balance sheet follows the equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. This equation must always hold true and ensures that the balance sheet is indeed balanced. The balance sheet thus provides a detailed and balanced snapshot of a company’s financial condition, illuminating its resources, obligations, and ownership structure.

Limitations of a Balance Sheet

Despite its essential role in financial analysis, the balance sheet does have several limitations that users should be aware of.

Firstly, the balance sheet is a snapshot of a company’s financial position at a specific point in time. This means it doesn’t reflect changes that occur between balance sheet dates. For example, the cash position can fluctuate significantly day to day, but the balance sheet only shows the amount of cash on hand at the close of business on the balance sheet date.

Secondly, many balance sheet items are based on historical cost, not current market value. This can distort the true value of assets like property, plant, and equipment if there have been significant changes in market values. Although some assets and liabilities may be reported at fair value, this is not universally applied across all items.

Another limitation is that not all assets and liabilities are reported on the balance sheet. Intangible assets like brand recognition, company reputation, and employee skills – often a significant source of value for a company – are not included unless they have been acquired. Similarly, potential liabilities or contingent liabilities, like lawsuits or environmental clean-up costs, may not be included if the outcome is uncertain or the amount cannot be reasonably estimated.

The balance sheet also relies on numerous estimates, assumptions, and judgments. For instance, deciding on depreciation methods, useful life estimates for long-lived assets, and allowances for doubtful accounts all require significant management judgment, which can introduce bias or error. Similarly, estimating the value of complex financial instruments or obligations can be challenging and subject to substantial uncertainty.

Additionally, the balance sheet does not provide information on cash flows. A company might show a strong balance sheet with plenty of assets and equity, but if it is not generating enough cash flow to meet its obligations, it could still face financial distress.

Lastly, it’s essential to note that a balance sheet can be manipulated through creative accounting practices or outright fraud, making it appear more favorable than the reality. Therefore, users must be cautious and consider other financial statements and information sources to corroborate the data on the balance sheet.

Balance sheet vs. Income statement

Both the balance sheet and the income statement are crucial financial statements, but they serve different purposes and offer distinct perspectives on a company’s financial status. Understanding the unique role of each can provide a more comprehensive picture of a company’s financial health.

Balance Sheet

As previously discussed, a balance sheet provides a snapshot of a company’s financial condition at a specific point in time. It shows the company’s assets (what it owns), liabilities (what it owes), and equity (the net assets belonging to the owners or shareholders).

Assets include things like cash, inventory, and property, while liabilities encompass debts such as loans, accounts payable, and accrued expenses. The equity section reveals the net value of the company, calculated by subtracting total liabilities from total assets.

A balance sheet follows the fundamental equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. This statement represents the cumulative result of all the company’s transactions from the time it began operations until the balance sheet date.

Income Statement

The income statement, also known as the profit and loss statement, provides a summary of a company’s revenues, costs, and expenses over a specific period—usually a fiscal quarter or year. Unlike the balance sheet’s point-in-time snapshot, the income statement offers a historical view covering a period.

Revenue, the top line of the income statement, is the income earned from the sale of goods or services. Costs and expenses are then subtracted to arrive at net income, the bottom line. Costs usually refer to the direct cost of producing goods sold (Cost of Goods Sold, or COGS), while expenses include operating expenses (like salaries, rent, and utilities), interest, and taxes.

The income statement essentially answers the question: “Did the company make a profit or suffer a loss over the period?”

Comparison

While both are crucial for assessing a company’s financial status, there are key differences:

- Timeframe: The balance sheet is a snapshot at a specific point in time, while the income statement covers a period (e.g., a quarter or year).

- Content: The balance sheet reports assets, liabilities, and equity, representing the company’s financial position. The income statement, however, shows revenues, costs, and expenses, reflecting the company’s financial performance over a period.

- Function: The balance sheet is used to evaluate a company’s liquidity and financial structure, while the income statement is used to assess profitability and operational performance.

- Connection: Changes in a company’s income statement are often reflected in the balance sheet. For instance, profits from the income statement increase equity on the balance sheet. Similarly, expenses may increase liabilities or decrease assets.

In summary, while the balance sheet and income statement serve different functions and provide different information, they are interconnected and together offer a more complete picture of a company’s financial health. For a thorough financial analysis, both statements should be examined and understood.

How to create a balance sheet?

Creating a balance sheet involves the organized collection and presentation of a company’s assets, liabilities, and equity. Here’s a step-by-step guide:

Step 1: Preparation

Gather all your financial information, including bank statements, invoices, receipts, and any other relevant documents. The accuracy of your balance sheet will depend on the accuracy of the information you’re using.

Step 2: Identify and Calculate Total Assets

Begin with your assets, which include both current and non-current assets.

- Current Assets: These are assets that can be converted into cash within one year. Examples include cash, accounts receivable, inventory, and short-term investments.

- Non-Current Assets: These are assets that cannot be easily converted into cash or are not expected to become cash within the next year. Examples include property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), long-term investments, and intangible assets.

Calculate the total value for each asset category, then add these up to get the total assets.

Step 3: Identify and Calculate Total Liabilities

Next, identify your current and non-current liabilities.

- Current Liabilities: These are obligations due within the next year. Examples include accounts payable, wages payable, and short-term loans.

- Non-Current Liabilities: These are obligations that are due beyond the next year. Examples include bonds payable, long-term lease obligations, and long-term loans.

Calculate the total value for each liability category, then add these up to get the total liabilities.

Step 4: Calculate Shareholder’s Equity

Shareholder’s equity can be calculated using the formula: Equity = Assets – Liabilities.

There are two main parts to equity:

- Share Capital: This is the money that shareholders have invested in the company.

- Retained Earnings: This is the net income that the company has earned over its life, minus any dividends distributed to shareholders.

Add up share capital and retained earnings to get total shareholder’s equity.

Step 5: Format the Balance Sheet

Your balance sheet should be structured in a way that clearly presents assets on one side and liabilities and equity on the other. The total assets should equal the total of liabilities and equity, reflecting the fundamental balance sheet equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity.

Step 6: Review and Analyze

Review your balance sheet for accuracy. Check that all calculations are correct and all items have been included. Analyze your balance sheet to understand your financial position. Look at your liquidity, solvency, and capital structure, and compare your current balance sheet with previous periods to identify trends.

Harnessing the Power of the Balance Sheet Template

The balance sheet template remains a vital instrument in your financial toolbox, serving as a reflection of your business’s current state and potential future trajectory. This tool is not just for internal scrutiny but also acts as a reliable source of information when engaging with external stakeholders. Amid the hustle and bustle of daily operations, money circulates in and out of your business like the constant ebb and flow of a tide.

Deciphering the pulse of your company’s health might sometimes feel like deciphering an intricate puzzle. The balance sheet, however, can act as a mirror reflecting your business’s financial status. Every balance sheet is akin to a portrait of your company’s financial wellbeing at a certain moment in time. Analyzing this financial snapshot allows you to probe into the intricate details of your company’s fiscal standing.

Moreover, this reflective snapshot furnishes you with a deeper understanding of your company’s overall robustness, paving the way for data-driven and insightful decision-making. In its essence, the balance sheet distills your key financial data for a specific date, providing a clear measure of your business’s liquidity and resilience.

Going beyond just a cash flow statement or profit and loss account, the balance sheet brings together the company’s revenue, equity, and expenditures to present a holistic view of your financial status. All this amalgamated information contained in one document aids you in unravelling the financial intricacies of your business more effectively.

In addition to shedding light on your internal operations, the balance sheet also assists you in addressing external challenges. For instance, when seeking a business loan, investors or lenders might request a glimpse of your balance sheet. Even your suppliers may gain newfound interest in your business upon scrutinizing your balance sheet, as it reveals your business’s stability and potential for longevity.

FAQs

Who prepares the balance sheet?

The balance sheet is typically prepared by the company’s accounting or finance department. It is the responsibility of the company’s management to ensure accurate and timely preparation of the balance sheet.

How often is a balance sheet prepared?

Balance sheets are typically prepared at the end of each accounting period, which is usually on a quarterly or annual basis. However, companies may choose to prepare interim balance sheets for shorter time periods to monitor their financial position more frequently.

Can a balance sheet show negative shareholders’ equity?

Yes, a balance sheet can show negative shareholders’ equity, which is often referred to as a deficit or accumulated losses. It occurs when a company’s accumulated losses or liabilities exceed its total assets and initial shareholders’ investment. Negative shareholders’ equity indicates financial distress or a significant decline in the company’s value.

How can an investor or creditor use the balance sheet?

Investors and creditors can use the balance sheet to assess a company’s financial health and make informed decisions. They can analyze the company’s liquidity, solvency, and financial stability by examining its assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity. The balance sheet, along with other financial statements and ratios, helps evaluate the company’s ability to generate profits, manage debt, and meet its financial obligations.

What are some examples of current assets on a balance sheet?

Current assets are assets that are expected to be converted into cash or used up within one year. Examples of current assets include:

- Cash and cash equivalents

- Short-term investments

- Accounts receivable

- Inventory

- Prepaid expenses

- Marketable securities

What are some examples of long-term assets on a balance sheet?

A: Long-term assets, also known as non-current assets or fixed assets, are assets that have a useful life of more than one year. Examples of long-term assets include:

- Property, plant, and equipment (e.g., buildings, machinery)

- Intangible assets (e.g., patents, trademarks)

- Long-term investments (e.g., stocks, bonds)

- Goodwill (the value of a company’s brand or reputation)

- Deferred tax assets

What are some examples of current liabilities on a balance sheet?

Current liabilities are obligations that are expected to be settled within one year. Examples of current liabilities include:

- Accounts payable

- Short-term loans and lines of credit

- Accrued expenses (e.g., salaries payable, utilities payable)

- Income taxes payable

- Customer deposits

- Current portion of long-term debt

What are some examples of long-term liabilities on a balance sheet?

Long-term liabilities are obligations that are due beyond one year. Examples of long-term liabilities include:

- Long-term loans and bonds payable

- Lease obligations

- Pension liabilities

- Deferred tax liabilities

- Deferred revenue

- Mortgage payable

![Free Printable Credit Card Authorization Form Templates [PDF, Word, Excel] 1 Credit Card Authorization Form](https://www.typecalendar.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Credit-Card-Authorization-Form-150x150.jpg)

![Free Printable Stock Ledger Templates [Excel,PDF, Word] 2 Stock Ledger](https://www.typecalendar.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Stock-Ledger-150x150.jpg)

![Free Printable Financial Projections Templates [Excel, PDF] 3 Financial Projection](https://www.typecalendar.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Financial-Projection-1-150x150.jpg)